What did Alice give to the fantasy genre?

With its respect for imagination and children, as well as the connections it makes between the two, Alice significantly influenced the direction of future children’s fantasy literature.

Wonderland pulls double duty in satirizing how adults treat children and representing the wonder that Alice’s imagination is capable of. Carroll chooses to end Alice on the latter idea, showing Alice’s older sister reflecting on her sister’s dream adventures.

...

Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would... keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood; and how she would gather about her other little children, and make their eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of wonderland of long ago; and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys...1

Alice shows a clear respect for fantasy for its own sake. Taking fantasy seriously can enliven a “dull reality,” and it can offer insight into others' experiences, highlighted by the adult Alice and her child listeneners relating to each other. According to Carroll, fantasy is essential for reaching the heart and enriching life.

Additionally, Carroll believes that the ability to create fantasy is deeply connected to childhood. A storyteller keeps the “heart of her childhood" and can put herself into a child’s point of view to reignite her imagination. As fantasy can help adults feel children’s “simple sorrows” and “simple joys,” Carroll argues that valuing fantasy can encourage respect for children’s experiences of the world and avoid didactic condescension.

This relation of fantasy to childhood would be instrumental in the formation of the modern fantasy genre, and as a definitive work of children’s fantasy, Alice became part of this.

Alice was not the first children’s book to believe in the importance of fantasy, and the nineteenth-century world was already shifting in that direction with the struggle between didacticism and imagination, the Romantic movement, and a growing fascination with medieval and folk literature. However, Alice’s high popularity amplified the ideas it reflected.

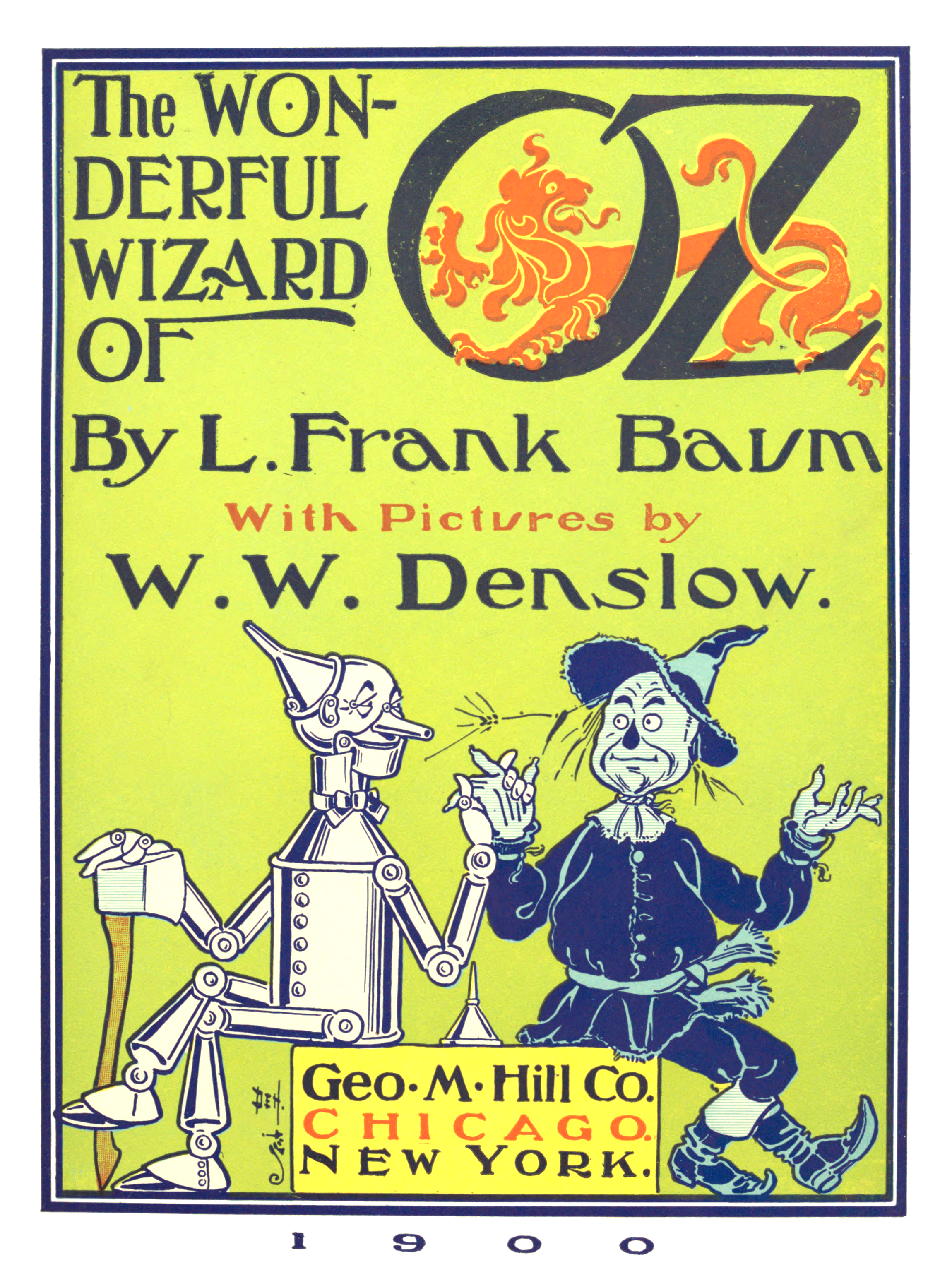

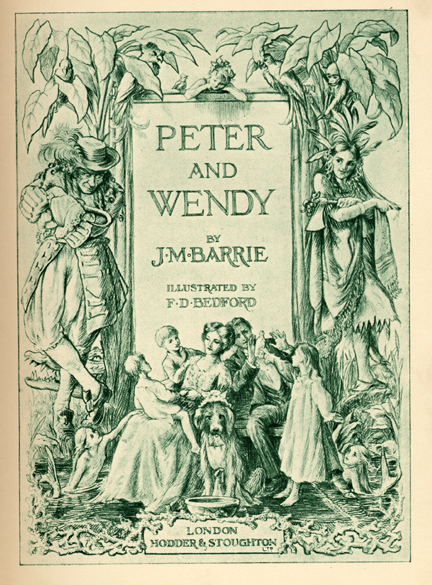

By the turn of the twentieth century, the association of children with fantasy had become the dominant view. Given Alice's stylistic influences on children’s fantasy like J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan works and L. Frank Baum’s Oz series—travel to another world, fairy tale inspiration, coming-of-age, and even a female protagonist (typically rare before Alice)—its ideas would have been inherited as well.

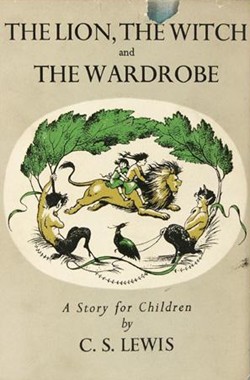

Twentieth-century fantasy pioneers such as J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis argued that “children raised on magical stories can … carry wonder in their hearts even after growing up into rational, modern adults.”2 Fantasy was looked down upon as out of place in a “mature” modern world, but these authors flipped the script. Fantasy’s association with childhood was its value. It could re-enchant the world.

Though these authors’ ideas about why fantasy was valuable were different—they were part of a backlash against modernity in both nostalgic and regressive ways—they still called back to the same ideas Carroll featured of fantasy and childhood as a connection with the heart in a “dull reality,” giving fantasy a new appeal to scholars and readers.

Even if indirectly, Alice helped to create a connection between the enchantment of fantasy and the enchantment of childhood. The idea that through fantasy, one can retain the “heart of… childhood” through the trials of growing up pushed fantasy into the prominence it has today.

Sources

1 Carroll, Alice in Wonderland, 104.

2 Cecire, Re-Enchanted, 18.